Descrizione

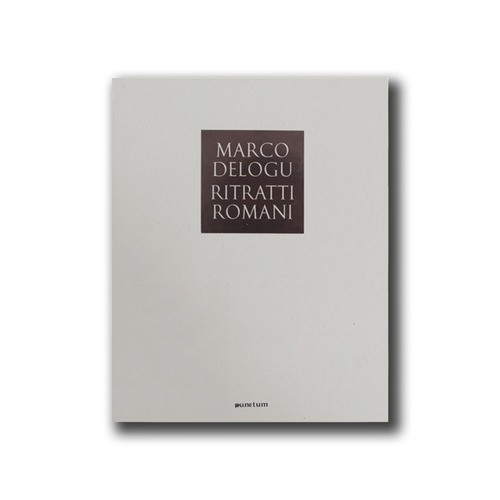

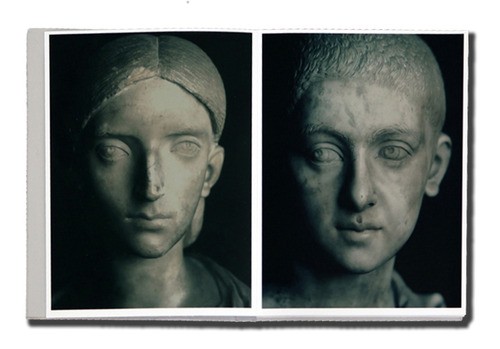

Countless hordes of tourists pass throught chilly galleries, without even glancing at the marbles exhibited on either side, unless they are marked with an asterisk in the guide-book. Everyone wants to see – and to say they have seen – the Mona Lisa, the Apollo Belvedere, the Night Watch. But no-one has time to stop and look at the faces of human beings who lived many centuries ago. Yet these faces bear similarities to those that could still be seen around Rome up until a few years ago. Now with immigration and the increasingly frequent mixing of races those features are disappearing. Inevitably when faced with things of the past we ask ourselves what we have in common with the people of centuries ago. Customs, taste, values, food, dress and daily routine have changed, but across the millennia the arrogance, anxiety, insecurity and awe before the mystery of life and death remain the same. The Roman portrait is linked to Hellenistic naturalism, we can trace its roots back to the Etruscan tradition or perhaps to the uncompromising realism of the wax masks that were made from the faces of the dead, whose features were thus preserved in the atrium of the home. It answered the need to confirm and leave a lasting memory of the self, a need which is fundamental to the human spirit. The same sentiments gave rise to the funerary inscription (when first among the upper classes and then among the humbler folk, there emerged a sense of the identity of self), which recorded the office, the years, months, days and even the hours of the deceased, as well as an account of his or her life. Roman art is narrative, it satisfies curiosity rather than aesthetic sensibility. When it does not possess the living image of a famous man, it invents one; thus a Homer, an Epicurus, a Cicero, not exactly as they were, but with features probably not unlike their own. Nowadays technology succours the spirit. Marco Delogu’s photographic eye seems gifted with psychological intuition. He has patiently observed beings who have been dead for millennia; their slight deformities, their melancholy, their awareness of approaching death. These ‘imaginary portraits’ are traced with extraordinary technical refinement, but above all with human compassion.